When Does a Startup Stop Being a Startup?

The term startup has become as widespread as it is vague. We use it to describe young, tech-driven, agile, disruptive companies—or simply those that still aren’t making money. But where do we draw the line? When does a startup stop being one and become, quite simply, a company?

“The answer isn’t as straightforward as it seems, and it depends on what you choose to measure: age, size, profitability, or level of uncertainty.”

This post is a continuation of Startup vs Company, where I began reflecting on the differences between both concepts. Here, I go deeper into the criteria that can help determine when a startup truly stops being one.

The Financial Criterion: The Maturity of the Numbers

One of the most common indicators is positive cash flow. In theory, when a company starts generating more cash than it consumes, it stops depending on investment rounds to survive.

But there are nuances. Amazon, for instance, took more than eight years to achieve positive operating cash flow. Does that mean it was still a startup all that time? If we look at its growth ambitions, reinvestment levels, and reliance on external capital, we might say yes. But considering its scale—it was already a listed multinational—the label starts to feel misplaced.

Cash flow is therefore a useful benchmark, but not a definitive one. A company can be profitable and still behave like a startup in terms of risk appetite, culture, or structure.

The Growth Criterion: From Exploration to Execution

Steve Blank, one of the fathers of lean startup thinking, defines a startup as “a temporary organization searching for a repeatable and scalable business model.”

Following that logic, the moment a company finds that model—when it stops experimenting and starts executing—it marks a clear shift in stage.

Take Glovo, for example. It could arguably be considered a startup until around 2020–2021, when it reached international scale, consolidated its logistics model, and began operating under more stable (and more regulated) corporate structures. Since then, it’s still young, but no longer “searching” for its model—it’s executing it. Albeit amid multiple tensions, the most relevant being regulatory pressure and the need to consolidate a market with too many competing players (too many players in the sector hinder the long-awaited profitability).

Conversely, some companies that have been around for years still fit the startup label because they haven’t yet validated their value proposition or path to profitability. Age, therefore, isn’t a decisive factor either.

The Organizational Criterion: Culture and Structure

Another way to assess it is from the inside.

A startup is often defined by its speed-oriented culture, tolerance for error, and flexible structure, where roles overlap and hierarchies blur.

“When an organization starts consolidating processes, internal policies, and control structures—not out of bureaucracy, but out of a need for stability—it’s transitioning from a ‘startup’ to a ‘company.’”

Spotify, for instance, maintained for years a tribe and squad culture—a hallmark of startup thinking. Today, it still innovates, but its structure and governance are those of a global corporation. The culture evolves with scale.

The Market Criterion: Perception and Narrative

Interestingly, the market (and the media) plays a role too.

Calling a company a startup acts as a kind of semantic shield. It allows for a certain leniency: if it’s still a startup, losses, operational chaos, or lack of focus are excused—under the promise of a brighter future.

Investors, however, are far less forgiving. When capital begins demanding profitability or predictability, the narrative changes. And at that point, even if the company keeps growing fast or retains a “startup look,” it’s playing a different game.

So, When Does It Stop Being One?

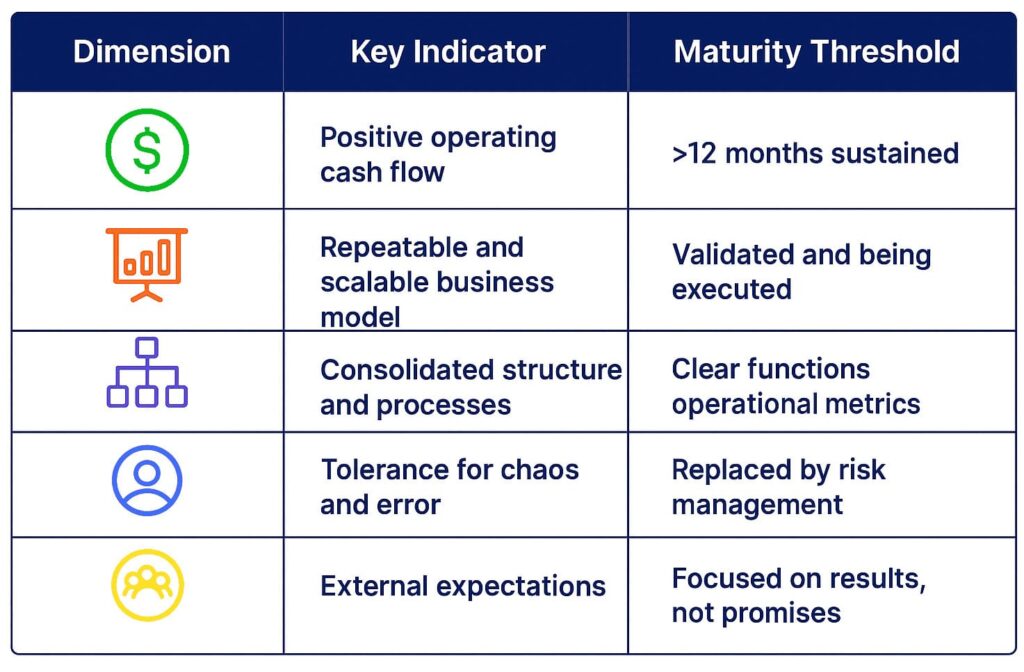

If we had to sum it up, we could use a combination of five key indicators: Financial, Business Model, Organization, Culture, and Market. The following table shows each of them along with the maturity threshold we assign to each:

If it meets three or more of these conditions, we’re probably no longer talking about a startup, but rather a company in expansion (scale-up) or consolidation.

More Than Just a Label

Perhaps the real question isn’t when a startup stops being one, but what it means to keep calling it that.

Sometimes, the label is used as an excuse to justify inefficiencies or immature decisions. Other times, it’s waved as a cultural flag to preserve agility. In both cases, the underlying issue remains the same: finding balance between ambition and responsibility.

Because, startup or not, there comes a moment when the numbers stop being promises, and have to start standing on their own.